I had a simple thought, and it ended up leading me down a winding road.

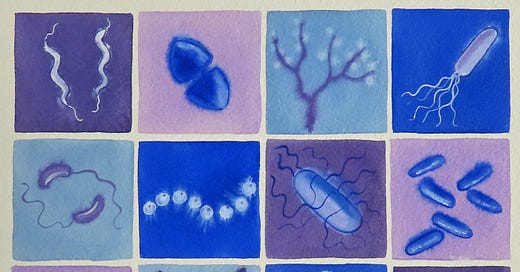

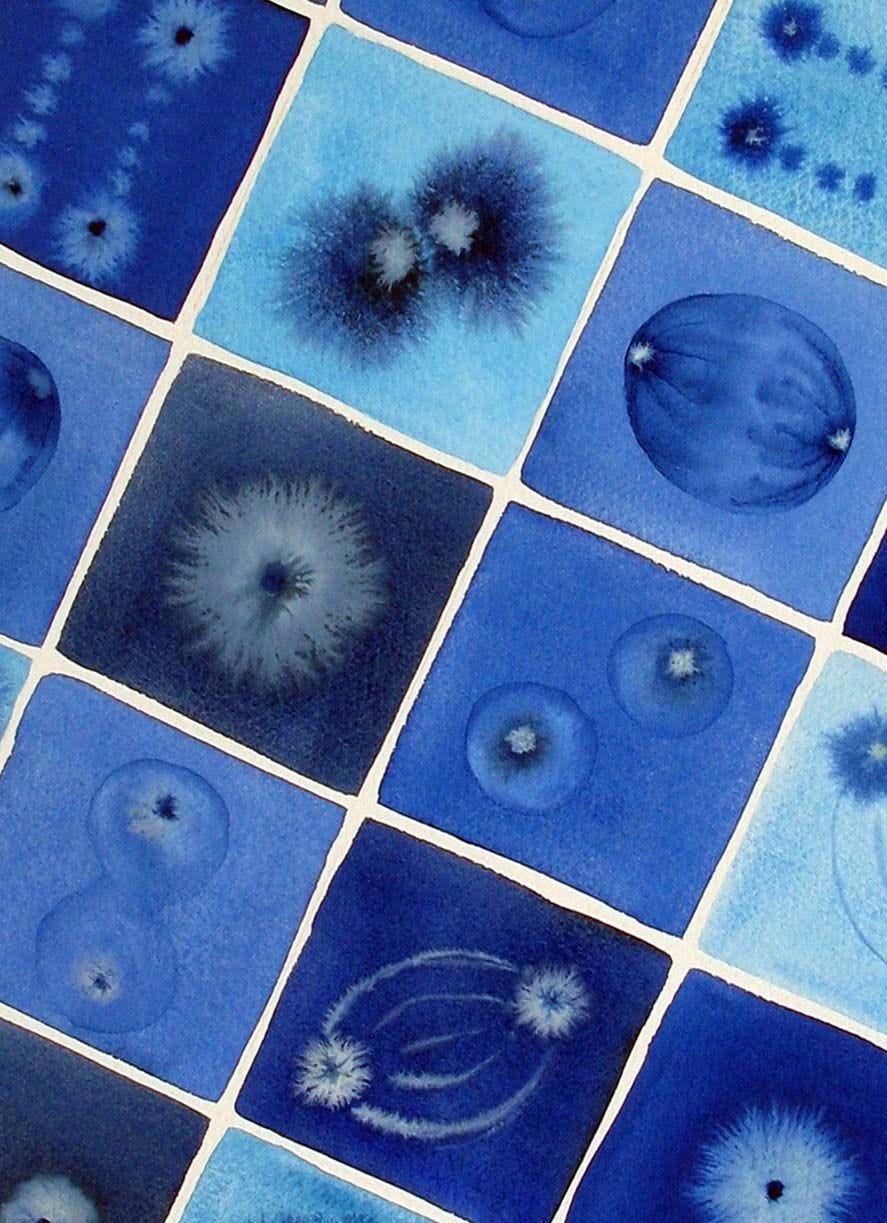

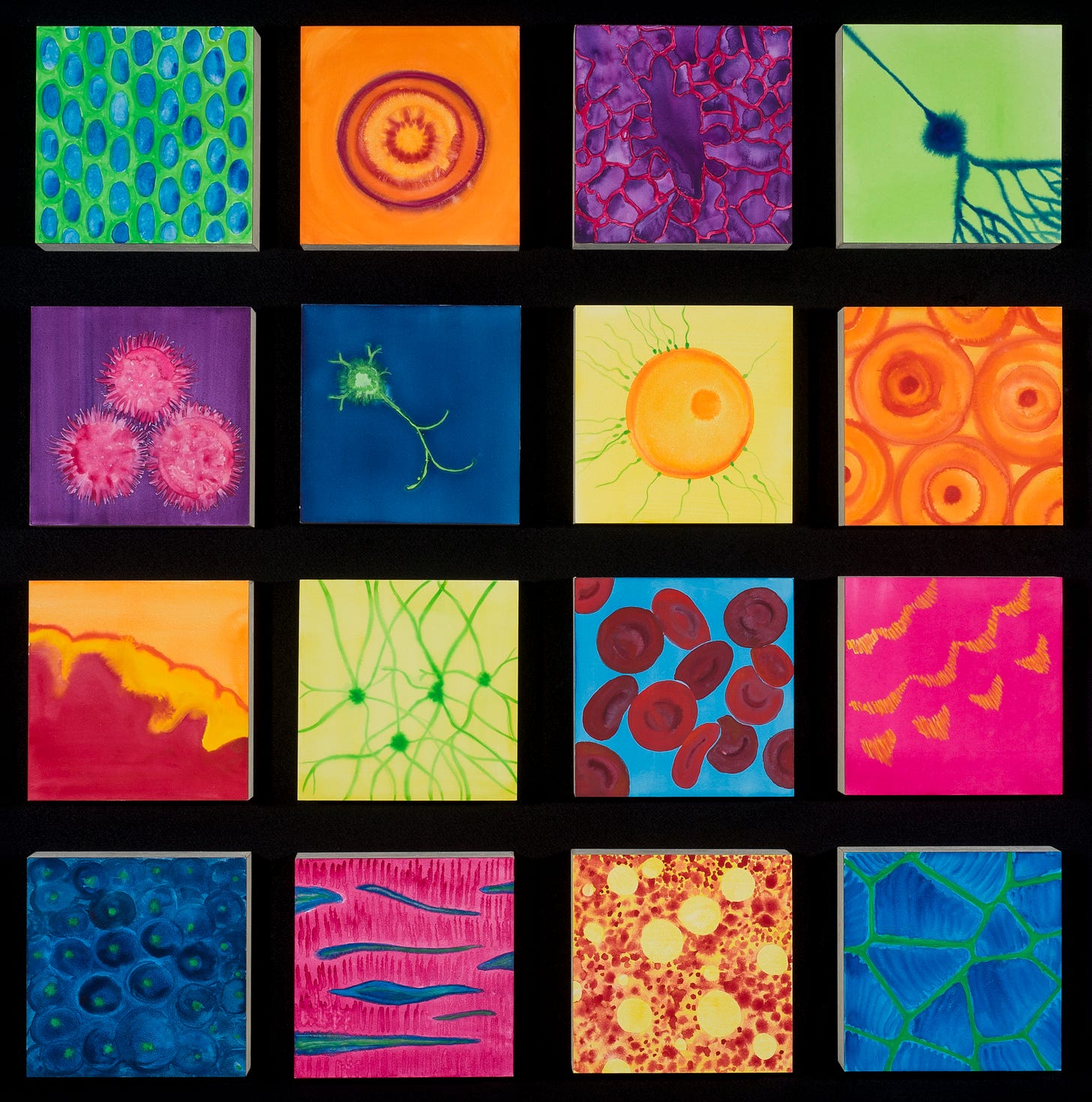

I thought I would write a post about grid paintings, because they are central to my art practice. I’ve been painting watercolor grids for more than 20 years now, and they continue to be among my most popular works.

I stumbled into my art career almost on a whim, with no education or training in art. Before I began painting, I was a minor-league intellectual, well-read and well-traveled, with a couple of degrees in the social sciences from some pretty fancy places.

But as an artist, I was completely self-taught, and for a long time I resisted developing an intellectual context for my artwork. Art writing seemed baffling and opaque, using phrases like “interrogating tropes” or “signifying non-being.” I remember hearing one well-known artist describe her work as “a deeply intuitive practice of mark-making” which struck me as a pretentious way of saying “I draw what I feel like drawing.”

It took me years to accept that there might be more to my work than just painting what I felt like painting. I see now that a lot of my resistance to art scholarship was reverse snobbery (I’m just a painter, I’m not one of those artsy people) and fear. Fear that I would not, could not, understand what 24-year-olds in MFA programs were talking about. Fear that it wasn’t the artspeak that was dumb, it was me.

So I’ve been dipping my toe into the literature. I’ve been reading more art writing, and thinking more about what underlies my work, and how it connects to the work of others. Which is why I decided to poke around for possible explanations about why my brain likes grids so much. And wow, did I get more than I bargained for.

I thought I was painting grids for three reasons. A practical reason: I use wet-in-wet watercolor, and breaking a painting up into small squares allows me to do that without ending up with a patch of color that is dry on one side and wet on the other. Also, leaving white space between the squares means I can let the paint bleed, but not all over the place. An aesthetic reason: creating a loose, organic shape inside a strict geometric shape creates a pleasing contrast. And finally, a thematic reason: when I started painting scientific images in grids, I liked the way they suggested the scientific method - repeating procedures, changing variables.

It turns out that there’s a lot more to grids than that. Writer Nessia Pope points out that “in modern life, the grid is everywhere,” from city streets to the keyboards of our computers, to the “tiny pixelated grids” of social media. “The grid is the net that connects art with the increasingly ordered qualities of day-to-day life.” Other writers note the connection of the grid to the shapes of windows, which are both transparent and reflective, and to the warp and weft of the loom, an archetype of craft and civilization.

But we can go even deeper than that.

In her influential 1979 essay, “Grids,” Rosalind Krauss declared the grid “an emblem of modernity,” omnipresent in the art of the 20th century. And she didn’t just mean that everyone from Kazimir Malevich to Agnes Martin had a thing for perpendicular lines.

In the cultist space of modern art, the grid serves not only as emblem but as myth. For like all myths, it deals with paradox or contradiction not by dissolving the paradox or resolving the contradiction, but by covering them over so that they seem (but only seem) to go away.

The grid’s mythic power is that it makes us able to think that we are dealing with materialism (or sometimes science, or logic) while at the same time it provides us with a release into belief (or illusion, or fiction). …

Although the grid is certainly not a story, it is a structure, and one, moreover, that allows a contradiction between the values of science and those of spiritualism to maintain themselves within the consciousness of modernism, or rather its unconscious, as something repressed.

Okay, that’s a lot, and I’m not sure I completely get it, but it made me think. I’m interested in the idea of a myth as something that allows us to create an appealing narrative about something we don’t fully understand. And in that sense, maybe the way we write about art serves that function too. Because we can talk about how looking at paintings excites the neurons, and we can discuss how artists use materials or techniques to create an emotional response, but I don’t think we can get all the way there, to explaining how looking at art makes you feel.

Let’s take an example. Why does the sun seem to move across the sky over the course of a day? Is it the rotation of the earth? Or is it a sun god driving a chariot? When it comes to how the structures of the eye process the marks on a canvas, we are clearly in “rotation of the earth” territory – we objectively know a lot about how it works. But why does the same painting cause anguish in one viewer and joy in another? We may still be at the sun god stage.

So maybe writing about art is, as Krauss wrote of the grid, a way of covering the space between what we can know (the scientific) and what we can only feel (the spiritual). There’s probably no way to make these things join up seamlessly, so we place a lattice of words on top to cover the messy bits or the blank spots. It may not be a golden chariot, but a crystalline phrase could bring us closer to the mysterious heart of art.

Thanks for reading. You can find my latest paintings here and my show schedule here.

If you enjoyed this piece, please share and subscribe, it’s free.

Thanks, I enjoyed it. We seem to have a similar story about “being from the outside,” except exchange visual art for music, and swap fancy degree in social sciences for fancy degree in hard sciences. I’ve worked on (unpaid) short films and tried to become a part of various music circles, including living a month in Berlin in 2018, but none of them really led anywhere on their own, much less to any kind of paid career yet. Maybe when you’re an outsider in one path, it also leads you towards being an outsider in other ones, even if part of the reason you left the first path was due to those conflicts and misalignments.

Wow. This is brilliant work.