Reading, writing and visual art intersect in profound and fascinating ways. In my last post I speed-walked through a few thousand years of history and quite a bit of science on this topic, but I skimped on the art. I’ll make up for that today, sharing the work of some contemporary visual artists using writing as a crucial element in their work.

The universal nature of early writing systems

Although they may not be up on the latest research on the evolution of writing, many artists seem to have an intuitive understanding of one key concept: that all alphabets are derived from basic visual patterns found in our environments. This means that even words in languages that we can’t read are comprehensible at some essential level.

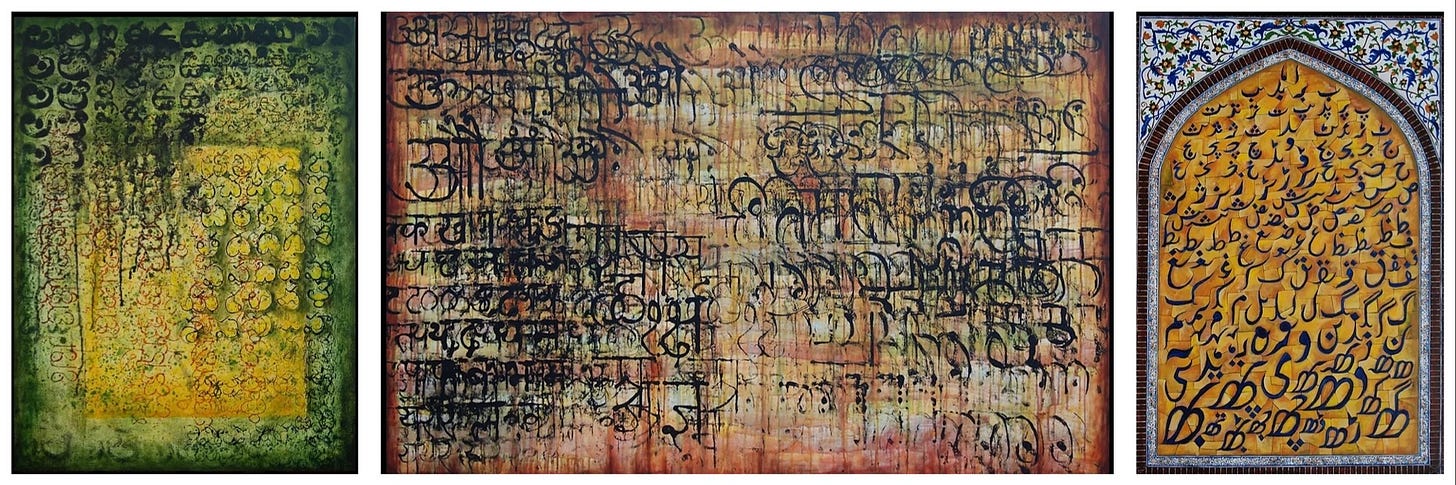

Iranian painter Maryam Ghanbarian, for example, senses “an unnatural and unnecessary gap between the universal appeal and understanding of certain shapes and forms and the shapes and forms of the alphabets used in different scripts and languages.” She sees her work, which juxtaposes calligraphic letter forms with organic shapes, as “an attempt at bridging this gap by creating an abstract representation of letters that flow together to tell a story.”

For Shanthi Chandrasekar, an Indian-born American artist whose work juxtaposes scientific principles with traditional artforms and spiritual themes, the connections to science are more explicit. In her Akshara (or syllable) series of paintings, she explores the evolution of the written forms of many Indian languages, most of which derive from the ancient Brahmi script, consisting of simple shapes. While her paintings attest to the exuberant variety of written scripts sprung from this ancient root, the full series retains a focus not on their differences but on what they share.

We see yet another approach in the work of Madiha Umar, a Syrian-born artist, for whom “Arabic letters were a vehicle of secular identity, a way of making Western painting her own.” A New York Times review notes that “(t)he bustling blue and red swooshes in an untitled 1978 watercolor clearly recall letter forms as well as ancient Mesopotamian crescent moons. But the way the crescents are organized, back and forth across the paper’s edges with an almost narrative motion, makes you think of writing, too,” an observation which brings us to an intriguing question:

Do we read a painting like a book?

This idea, that we “read” a painting like a book page – or not – informs the work of many artists. When critic Clement Greenberg observed that Picasso “sees the picture as a wall, while [Paul] Klee sees it as a page,” he did not mean it as a compliment to Klee. And yet, even as the Picasso style dominated the past century, Klee was not alone in sensing a kinship between painting and page.

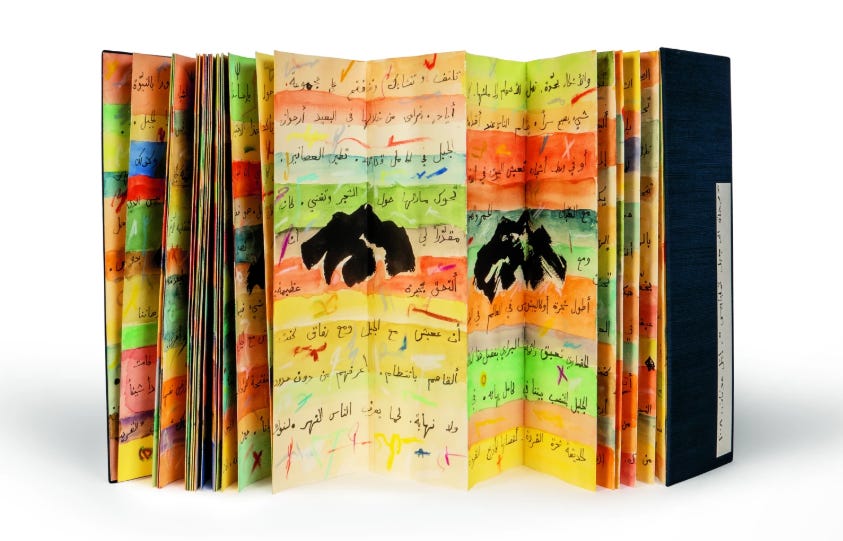

A literal example of “painting as page” is the work of Lebanese artist Etel Adnan, who often painted in sketchbooks or on book-like constructions of folded paper, incorporating poetry or text-like signs. Adnan observed that “in Japanese and Chinese culture, traditionally, you don’t have images on the wall, but in books. You open a drawer, take out a book – you’re able to look for as long as you want. The gesture of looking at an image, and the way you read a poem, gets closer to an affinity between the arts. You understand that visual art is a matter of meditation, like a poem.”

Yet this “affinity between the arts” is also embodied in the Cold Mountain series by iconic American artist Brice Marden, a “wall” guy if there ever was one. The paintings are based on a collection of Chinese poems written about 700 AD by a hermit poet named Han Shan. Marden recalled, “they’re landscape oriented poems. I based these paintings on the form of the poems. I worked them the same way you write Chinese, from top to bottom, right to left, and it worked very good for me because I’m left-handed, so I didn’t smear or anything as I was going across.”

Marden produced these paintings, which strikingly resemble calligraphy, by applying paint with a stick in a writing-like gesture. He then removed some of the paint and layered more “writing” over the top, leaving the layers below partly visible. The fact that the artist mentions his left-handedness as a factor in the creation of these pieces brings us to another important factor in the interplay of writing and art: the hand of the artist.

The Hand and The Gesture

Writing is drawing, drawing is writing. Because it’s the same gesture. They’re close already. - Etel Adnan

Adnan recalled how the arrival of a letter was once a significantly more eloquent event than the receipt of an email. Many factors - handwriting, language, ink color, paper choice, even the age and mood of the writer - affected the feeling and meaning of the text, information that has disappeared in the age of email. Could art that evokes writing recapture some of the emotion that the written word itself has lost in the screen age?

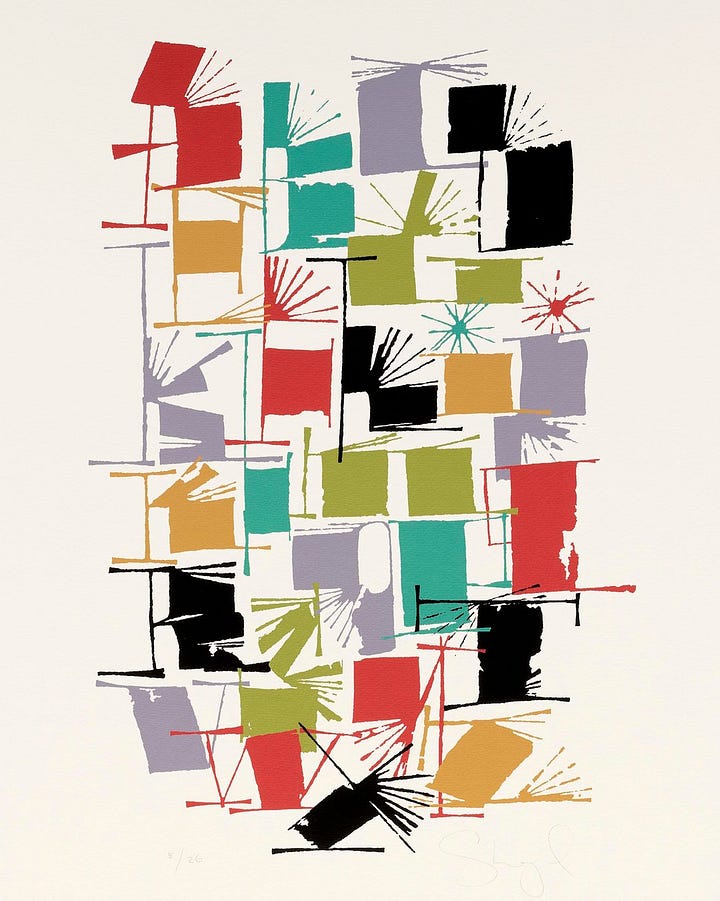

To the innovative calligrapher Susan Skarsgård, “the inherent beauty of an expressive line, written with the indelible gesture of a human hand” is the thread that unites her work. In her 2009 print series 26 of 26, Skarsgård created 26 dazzlingly different versions of the English alphabet, “compositions that explore shape, negative space, rhythm, pattern, color, texture and perception.”

Interestingly, Skarsgård employs a scientific metaphor to describe her alphabet-inspired artwork. ‘The familiar shapes of the alphabet, taken down to their elemental form and stripped of their meaning, have always been intriguing to me,’ she explains. ‘Somewhat like arranging the DNA of language and looking at it purely as shape and form.’

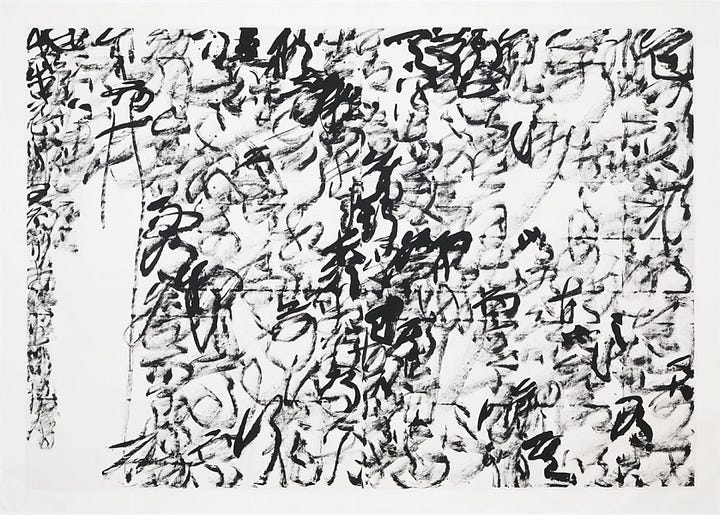

The final artist I’ll highlight here takes the familiar gesture of writing into full-body performance. Chinese artist Wang Dongling “exposes the work of art as shaped directly by the artist's reach, stamina, and physical movement…Wang liberates calligraphic gesture, form and space from the bounds of text.” Wang often makes his work in front of an audience, using a broom-sized brush on a paper-covered floor, writing out traditional Chinese texts but rendering them in what he calls “chaos script” – calligraphy so unreadable it becomes pure abstraction.

In the hundred years between Paul Klee and Wang Dongling, worldwide literacy rates increased massively, so that reading and writing became experiences common to almost all. It makes sense that artists of the past century would seek to understand and convey this experience - at once ancient and modern, universal and deeply personal - in distinctively visual ways. Now, as the idea of writing by hand becomes increasingly dated and quaint, we begin to see artists’ explorations of these concepts evolve as well.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this piece, please share and subscribe. I’ll be back in a couple of weeks with some scientific art that’s closer to home.

You can support my work by buying my art.