A couple of weeks ago, as I wandered the internet looking for art opportunities, I stumbled upon a call for art for a new hospital. It grabbed my attention, as hospitals generally have both money and enormous expanses of wall, things painters often lack. As I read on, though, my enthusiasm cooled. The curators had a long list of precise stipulations about the art they were looking for, and it didn’t include watercolor viruses:

Art should be peaceful, joyful, relaxing, and emit a sense of pride in location

Art should capture the magnificence of mother nature

Art should be a celebration of nature, not a simple documentation

Art should have interest through texture, color, depth, shadow, & line

Art should not be boring, flat, uninteresting, or dull

Art should not depict death or dying

Art should not be dark or foreboding

Avoid images with high noon skies without clouds

Avoid dark evening images

Avoid images with empty seats such as benches

Avoid images of just clouds

Avoid large murals with oversized objects such as fruits

Avoid florals with dead leaves and buds

Okay, got it. Landscapes, at midmorning, or possibly midafternoon, with a few fluffy clouds. Proud. Magnificent. Not too dark or too bright. Lots of texture. Flowers and leaves are okay, but only very fresh ones. No benches. No fruit. Wait, no fruit? What?

I was puzzled because I have sold quite a few paintings to hospitals, and my paintings generally feature things like viruses, bacteria, and brains, which would appear to be non-starters for this call. In fact, one of my rare pieces to depict cancerous cells sold to a doctor at a prominent children’s hospital. My very first institutional sale was to Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, DC, and the curator there told me they liked my work because “it looked like things under the microscope, but friendly.”

So clearly, opinions differ on what types of art people want to see at a hospital.

A few days after spotting the call, I learned something about just how much those opinions differ, and how much they have shifted over the past 100 years. I attended a panel discussion featuring Rick Luftglass, where he talked about the book Healing Walls, about historic and contemporary art in New York hospitals. It was eye-opening!

During the WPA era in the 1930s, the government hired artists to paint murals for many hospitals. A lot of them featured images of doctors and nurses at work, like this busy panorama by William Palmer for Queens General Hospital, where patients enter in distress at left and leave fully healed at right, after having passed through what seems like dozens of medical and surgical procedures. Personally, I am not comforted by the idea of this many medical professionals jammed into tiny rooms.

A more fantastical vision emerges from Walter Quirt’s The Growth of Medicine from Primitive Times, a surrealistic 1938 mural for New York’s Bellevue Hospital that features many nude bodies, some cut-up corpses, a rhino, and a tree growing skulls. I think it might run afoul of the instruction that “art should not be dark or foreboding.”

I should note that many of the WPA-era murals were intended for staff-only areas of hospitals, such as dining rooms and lecture halls, rather than for public spaces. But even in patient care areas, the art could startle, as shown by this extremely non-soothing mural by Abram Champanier, made for the children’s ward of Gouverneur Hospital. Yikes! Well, it’s not boring or dull.

The 21st century murals featured in Healing Walls reflect not only changing artistic taste, but a deeper understanding of how art and the built environment can affect the mental well-being of patients, families, and healthcare workers. In these murals, healthcare workers are depicted as caring community members, rather than godlike beings doing inscrutable things to passive patients. I’m no expert, but it seems obvious that most people going to the hospital would rather think about something other than the procedure they or their loved one is undergoing. So yes, some of the murals portray scenes of beautiful nature in bright, saturated tones.

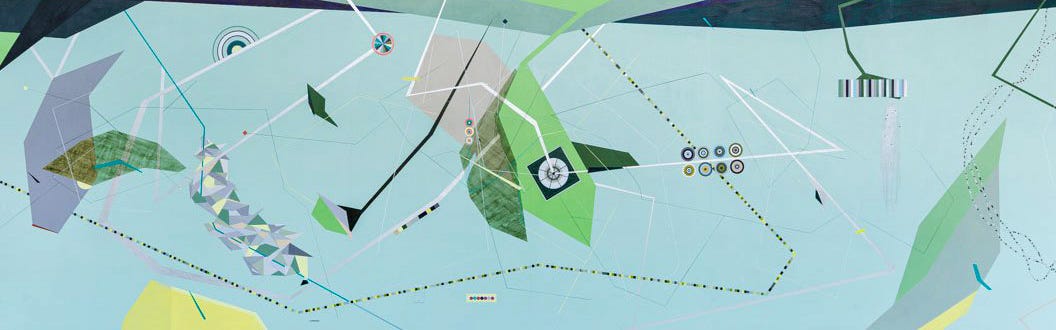

But many of them are abstract, trusting their audience to enjoy the interplay of line, color, and shape, to feel the energy and rhythm of a painting without relying on familiar images. My favorite is this mural by Dannielle Tegeder, The Emerald Constellation Force Between us and Before Us, made for a hospital in Queens in 2020, in the throes of the COVID pandemic.

Here’s how the artist describes her concept for the piece: “The lobby is the nucleus. Patients enter and are immediately thrust into this complex web of care, interacting with nurses, doctors, staff and other patients. Most times, these patients are in moments of distress. The mural is intended to help them realize that they are part of a larger picture that extends beyond themselves and their current state, and that they are never alone.“

The color palette, at once calm and vibrant, was chosen with input from hospital staff. The images are intriguing but in no way menacing or upsetting. You could look at this for a long time, letting your mind’s eye trace the linear paths, and never be bored.

And that, to me, is a beautiful example of what hospital art can be.

This is really interesting, love it. As a musician, I've also thought a lot about this over time, especially in context of the usually mindless muzak that's piped into hospitals, waiting rooms, dentist offices, and above all, restaurants, which are all designed to conjure some type of mental behavior or state, but mostly just annoy me with their generic mediocrity, in most cases.

Great piece Michele! Yes some commissioners write a brief that totally infantilises hospital users and then wonder why they get bland art.