A question keeps bubbling up in my conversations lately: how much information do artists owe their audience? Should artists spell out their intentions, inspirations, and techniques when exhibiting their work, or should they simply put the art into the world for others to interpret?

Let me preface this by saying that many people with more expertise than I have considered these questions and debated them at length. My goal here is to tell a few relevant stories and provide some food for thought. Please note that I am not the artist in these anecdotes.

Story 1: The Q & A period of a talk at an exhibition of science-inspired artwork

Despite having just heard a talk by the artist that delved deeply into the work, audience members insisted that they wanted written explanations of the science behind the art. The artist and the curator explained that wall text was controversial in art spaces because there was always a danger of imposing a certain viewpoint, when art should be open to many interpretations. The audience members did not seem satisfied with this response.

After the talk, another artist complained to me about how people wanted to be “spoon-fed” explanations of artwork, and artists are now expected to produce statements excavating the influences and concepts behind their work. The artist felt strongly that people should be allowed to approach art without any preconceptions.

Story 2: A conference panel on the intersection of science and art

A scientist worked with an artist to produce a science-inspired work for a public festival. The artist was clear that they wanted people to approach the work without explanatory text, but the scientist, sensing that some people did not fully understand the installation, decided to jump in and start explaining the work to viewers. I was shocked that the scientist would ignore the artist’s wishes, but the scientist was adamant that they were correct, and that people were very grateful for the information. The artist wanted people to encounter the installation as art, not as science communication, an idea the scientist didn’t seem to grasp.

Stories like this remind me of when the NFL experimented with an “announcerless game” in response to complaints that their commentators talked too much, and that fans just wanted to watch the action. The no-commentary game was a flop: most NFL fans wanted to be told what was happening.

But when NFL players and coaches watch games, they don’t use the standard network tape. They get zoomed-out overhead shots so they can see the movement of all 22 players on the field, and they don’t need Troy Aikman to explain the play or how the defense reacted. To extend this comparison to art: maybe artists and serious art lovers want the “pro” version. They either know what they’re looking at and are comfortable with their own assessments, or they enjoy the stimulating sense of uncertainty.

Most people looking at art, however, like most people watching football, prefer a little more context and expert commentary. This may be especially true with science-inspired art, where people are generally less familiar with the underlying scientific concepts. Everyone understands landscape painting; not everyone relates to artwork based on quantum mechanics. It’s already hard enough getting people to look at art. Why not provide the type of support audiences want?

At the same time, I am sympathetic to the views of artists and curators. If you’re lucky, you’ve had the experience of stumbling upon a work of art that evoked a strong emotional reaction. Now imagine that moments before encountering that artwork, you read a wall text about it that reminded you of your ex, or of your fifth-grade bully. Words that provide helpful context for one viewer might be confusing or offensive to another. It’s incredibly difficult for exhibition text to provide commentary that doesn’t impose some kind of opinion. Why not let people approach the work without interpretation?

I don’t think there’s a simple answer, so I suggest meeting in the middle (punt!)

As most viewers seem to prefer explanatory wall text, I believe artists and curators should, in most cases, provide it. Nobody can force anyone to read it, after all, just as people who dislike commentary are free to watch football games on mute. On the other hand, if an artist or curator feels strongly that wall text is intrusive or inappropriate for a given exhibition, viewers should respect that and be open to the unmediated experience. They might discover unexpected insights, all on their own.

And now a word about me:

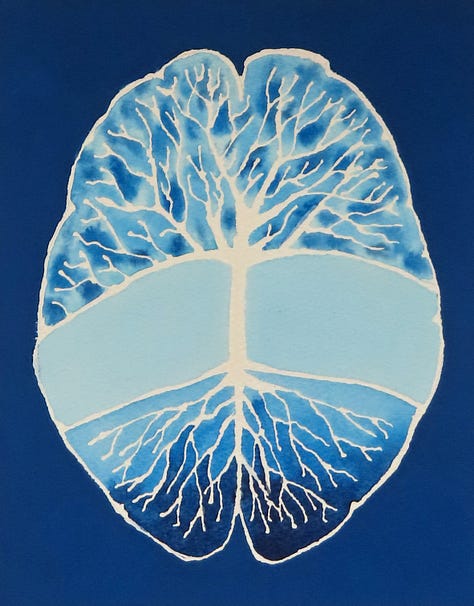

I’ve been very busy painting brains and neurons in ink and watercolor. Some of them will be coming with me to Chicago for the Society for Neuroscience meeting in early October, but you can find some in my shop now.

If you’re in the DC area, you can find me at this event in Van Ness on September 14 and at the Downtown Hyattsville Arts Festival on September 21.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please share.

Beautiful brains, Michele. And you make a good point about some of us wanting the pro version.

As an artist working with abstraction based on personal observations and experiences, I find that giving viewers some idea of what's behind the work in my artist statements can help them connect with the work a bit more than if I don't. I'm not talking about hand-holding and explaining everything, that would deaden the experience for the viewer (and myself).

Giving viewers pathways into the work with information about some of my influences and observations, and sometimes titles, while leaving things for them to discover on their own makes for a better art experience for them. I don't say anything about my "intentions" because once art is out in the world, it's meanings changes depending on who is experiencing it.